35. Optimal Growth II: Time Iteration#

Contents

35.1. Overview#

In this lecture we’ll continue our earlier study of the stochastic optimal growth model.

In that lecture we solved the associated discounted dynamic programming problem using value function iteration.

The beauty of this technique is its broad applicability.

With numerical problems, however, we can often attain higher efficiency in specific applications by deriving methods that are carefully tailored to the application at hand.

The stochastic optimal growth model has plenty of structure to exploit for this purpose, especially when we adopt some concavity and smoothness assumptions over primitives.

We’ll use this structure to obtain an Euler equation based method that’s more efficient than value function iteration for this and some other closely related applications.

In a subsequent lecture we’ll see that the numerical implementation part of the Euler equation method can be further adjusted to obtain even more efficiency.

35.2. The Euler Equation#

Let’s take the model set out in the stochastic growth model lecture and add the assumptions that

The last two conditions are usually called Inada conditions.

Recall the Bellman equation

Let the optimal consumption policy be denoted by

We know that

The conditions above imply that

the optimal policy is continuous, strictly increasing and also interior, in the sense that

the value function is strictly concave and continuously differentiable, with

The last result is called the envelope condition due to its relationship with the envelope theorem.

To see why (35.2) might be valid, write the Bellman equation in the equivalent form

differentiate naively with respect to

Section 12.1 of EDTC contains full proofs of these results, and closely related discussions can be found in many other texts.

Differentiability of the value function and iteriority of the optimal policy imply that optimal consumption satisfies the first order condition associated with (35.1), which is

Combining (35.2) and the first-order condition (35.3) gives the famous Euler equation

We can think of the Euler equation as a functional equation

over interior consumption policies

Our aim is to solve the functional equation (35.5) and hence obtain

35.2.1. The Coleman Operator#

Recall the Bellman operator

Just as we introduced the Bellman operator to solve the Bellman equation, we will now introduce an operator over policies to help us solve the Euler equation.

This operator

Henceforth we denote this set of policies by

The operator

returns a new function

We call this operator the Coleman operator to acknowledge the work of [Col90] (although many people have studied this and other closely related iterative techniques).

In essence,

The important thing to note about

In particular, the optimal policy

Indeed, for fixed

In view of the Euler equation, this is exactly

35.2.2. Is the Coleman Operator Well Defined?#

In particular, is there always a unique

The answer is yes, under our assumptions.

For any

is continuous and strictly increasing in

diverges to

The left side of (35.7)

is continuous and strictly decreasing in

diverges to

Sketching these curves and using the information above will convince you that they cross exactly once as

With a bit more analysis, one can show in addition that

35.3. Comparison with Value Function Iteration#

How does Euler equation time iteration compare with value function iteration?

Both can be used to compute the optimal policy, but is one faster or more accurate?

There are two parts to this story.

First, on a theoretical level, the two methods are essentially isomorphic.

In particular, they converge at the same rate.

We’ll prove this in just a moment.

The other side to the story is the speed of the numerical implementation.

It turns out that, once we actually implement these two routines, time iteration is faster and more accurate than value function iteration.

35.3.1. Equivalent Dynamics#

Let’s talk about the theory first.

To explain the connection between the two algorithms, it helps to understand the notion of equivalent dynamics.

(This concept is very helpful in many other contexts as well).

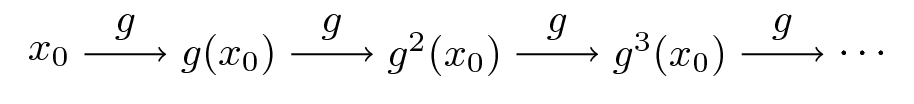

Suppose that we have a function

The pair

Equivalently,

Here’s the picture

Now let another function

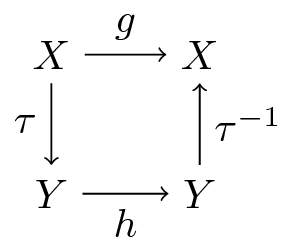

Suppose further that

there exists a bijection

the two functions commute under

The last statement can be written more simply as

or, by applying

Here’s a commutative diagram that illustrates

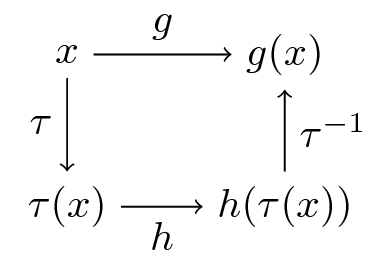

Here’s a similar figure that traces out the action of the maps on a point

Now, it’s easy to check from (35.8) that

In fact, if you like proofs by induction, you won’t have trouble showing that

is valid for all

What does this tell us?

It tells us that the following are equivalent

iterate

shift

We end up with exactly the same object.

35.3.2. Back to Economics#

Have you guessed where this is leading?

What we’re going to show now is that the operators

The implication is that they have exactly the same rate of convergence.

To make life a little easier, we’ll assume in the following analysis (although not

always in our applications) that

35.3.2.1. A Bijection#

Let

For

Although we omit details,

See proposition 12.1.18 of EDTC

It turns out that

A (solved) exercise below asks you to confirm this.

35.3.2.2. Commutative Operators#

It is an additional solved exercise (see below) to show that

In view of the preceding discussion, this implies that

Hence,

35.4. Implementation#

We’ve just shown that the operators

However, it turns out that, once numerical approximation is taken into account, significant differences arises.

In particular, the image of policy functions under

Our intuition for this result is that

the Coleman operator exploits more information because it uses first order and envelope conditions

policy functions generally have less curvature than value functions, and hence admit more accurate approximations based on grid point information

35.4.1. The Operator#

Here’s some code that implements the Coleman operator.

using LinearAlgebra, Statistics

using BenchmarkTools, Interpolations, LaTeXStrings, Plots, Roots

using Optim, Random

using BenchmarkTools, Interpolations, Plots, Roots

function K!(Kg, g, grid, beta, dudc, f, f_prime, shocks)

# This function requires the container of the output value as argument Kg

# Construct linear interpolation object

g_func = LinearInterpolation(grid, g, extrapolation_bc = Line())

# solve for updated consumption value

for (i, y) in enumerate(grid)

function h(c)

vals = dudc.(g_func.(f(y - c) * shocks)) .* f_prime(y - c) .* shocks

return dudc(c) - beta * mean(vals)

end

Kg[i] = find_zero(h, (1e-10, y - 1e-10))

end

return Kg

end

# The following function does NOT require the container of the output value as argument

function K(g, grid, beta, dudc, f, f_prime, shocks)

K!(similar(g), g, grid, beta, dudc, f, f_prime, shocks)

end

K (generic function with 1 method)

It has some similarities to the code for the Bellman operator in our optimal growth lecture.

For example, it evaluates integrals by Monte Carlo and approximates functions using linear interpolation.

Here’s that Bellman operator code again, which needs to be executed because we’ll use it in some tests below

using Optim

function T(w, grid, beta, u, f, shocks, Tw = similar(w);

compute_policy = false)

# apply linear interpolation to w

w_func = LinearInterpolation(grid, w, extrapolation_bc = Line())

if compute_policy

sigma = similar(w)

end

# set Tw[i] = max_c { u(c) + beta E w(f(y - c) z)}

for (i, y) in enumerate(grid)

objective(c) = u(c) + beta * mean(w_func.(f(y - c) .* shocks))

res = maximize(objective, 1e-10, y)

if compute_policy

sigma[i] = Optim.maximizer(res)

end

Tw[i] = Optim.maximum(res)

end

if compute_policy

return Tw, sigma

else

return Tw

end

end

T (generic function with 2 methods)

35.4.2. Testing on the Log / Cobb–Douglas case#

As we did for value function iteration, let’s start by testing our method in the presence of a model that does have an analytical solution.

Here’s an object containing data from the log-linear growth model we used in the value function iteration lecture

isoelastic(c, gamma) = isone(gamma) ? log(c) : (c^(1 - gamma) - 1) / (1 - gamma)

function Model(; alpha = 0.65, # Productivity parameter

beta = 0.95, # Discount factor

gamma = 1.0, # Risk aversion

mu = 0.0, # First parameter in lognorm(mu, sigma)

s = 0.1, # Second parameter in lognorm(mu, sigma)

grid = range(1e-6, 4, length = 200), # Grid

grid_min = 1e-6, # Smallest grid point

grid_max = 4.0, # Largest grid point

grid_size = 200, # Number of grid points

u = (c, gamma = gamma) -> isoelastic(c, gamma), # utility function

dudc = c -> c^(-gamma), # u_prime

f = k -> k^alpha, # production function

f_prime = k -> alpha * k^(alpha - 1))

return (; alpha, beta, gamma, mu, s, grid, grid_min, grid_max, grid_size, u,

dudc, f, f_prime)

end

Model (generic function with 1 method)

Next we generate an instance

m = Model();

We also need some shock draws for Monte Carlo integration

using Random

Random.seed!(42) # for reproducible results.

shock_size = 250 # number of shock draws in Monte Carlo integral

shocks = collect(exp.(m.mu .+ m.s * randn(shock_size))); # generate shocks

As a preliminary test, let’s see if

function verify_true_policy(m, shocks, c_star)

# compute (Kc_star)

(; grid, beta, dudc, f, f_prime) = m

c_star_new = K(c_star, grid, beta, dudc, f, f_prime, shocks)

# plot c_star and Kc_star

plot(grid, c_star, label = L"optimal policy $c^*$")

plot!(grid, c_star_new, label = L"Kc^*")

plot!(legend = :topleft)

end

verify_true_policy (generic function with 1 method)

c_star = (1 - m.alpha * m.beta) * m.grid # true policy (c_star)

verify_true_policy(m, shocks, c_star)

We can’t really distinguish the two plots, so we are looking good, at least for this test.

Next let’s try iterating from an arbitrary initial condition and see if we

converge towards

The initial condition we’ll use is the one that eats the whole pie:

function check_convergence(m, shocks, c_star, g_init; n_iter = 15)

(; grid, beta, dudc, f, f_prime) = m

g = g_init

plot(m.grid, g, lw = 2, alpha = 0.6, label = L"intial condition $c(y) = y$")

for i in 1:n_iter

new_g = K(g, grid, beta, dudc, f, f_prime, shocks)

g = new_g

plot!(grid, g, lw = 2, alpha = 0.6, label = "")

end

plot!(grid, c_star, color = :black, lw = 2, alpha = 0.8,

label = L"true policy function $c^*$")

plot!(legend = :topleft)

end

check_convergence (generic function with 1 method)

check_convergence(m, shocks, c_star, m.grid, n_iter = 15)

We see that the policy has converged nicely, in only a few steps.

Now let’s compare the accuracy of iteration using the Coleman and Bellman operators.

We’ll generate

In each case we’ll compare the resulting policy to

The theory on equivalent dynamics says we will get the same policy function and hence the same errors.

But in fact we expect the first method to be more accurate for reasons discussed above

function iterate_updating(func, arg_init; sim_length = 20)

arg = arg_init

for i in 1:sim_length

new_arg = func(arg)

arg = new_arg

end

return arg

end

function compare_error(m, shocks, g_init, w_init; sim_length = 20)

(; grid, beta, u, dudc, f, f_prime) = m

g, w = g_init, w_init

# two functions for simplification

bellman_single_arg(w) = T(w, grid, beta, u, f, shocks)

coleman_single_arg(g) = K(g, grid, beta, dudc, f, f_prime, shocks)

g = iterate_updating(coleman_single_arg, grid, sim_length = 20)

w = iterate_updating(bellman_single_arg, u.(grid), sim_length = 20)

new_w, vf_g = T(w, grid, beta, u, f, shocks, compute_policy = true)

pf_error = c_star - g

vf_error = c_star - vf_g

plot(grid, zero(grid), color = :black, lw = 1, label = "")

plot!(grid, pf_error, lw = 2, alpha = 0.6, label = "policy iteration error")

plot!(grid, vf_error, lw = 2, alpha = 0.6, label = "value iteration error")

plot!(legend = :bottomleft)

end

compare_error (generic function with 1 method)

compare_error(m, shocks, m.grid, m.u.(m.grid), sim_length = 20)

As you can see, time iteration is much more accurate for a given number of iterations.

35.5. Exercises#

35.5.1. Exercise 1#

Show that (35.9) is valid. In particular,

Let

Fix

35.5.2. Exercise 2#

Show that

35.5.3. Exercise 3#

Consider the same model as above but with the CRRA utility function

Iterate 20 times with Bellman iteration and Euler equation time iteration

start time iteration from

start value function iteration from

set

Compare the resulting policies and check that they are close.

35.5.4. Exercise 4#

Do the same exercise, but now, rather than plotting results, benchmark both approaches with 20 iterations.

35.6. Solutions#

35.6.1. Solution to Exercise 1#

Let

Using the envelope theorem, one can show that

Hence

On the other hand,

We see that

35.6.2. Solution to Exercise 2#

We need to show that

To see this, first observe that, in view of our assumptions above,

It follows that

Moreover, for fixed

Hence, for fixed

Moreover, interiority holds because

In particular,

To see that each

Let

With a small amount of effort you will be able to show that

It’s also true that

To see this, suppose that

Then

The fundamental theorem of calculus then implies that

35.6.3. Solution to Exercise 3#

Here’s the code, which will execute if you’ve run all the code above

# Model instance with risk aversion = 1.5

# others are the same as the previous instance

m_ex = Model(gamma = 1.5);

function exercise2(m, shocks, g_init = m.grid, w_init = m.u.(m.grid);

sim_length = 20)

(; grid, beta, u, dudc, f, f_prime) = m

# initial policy and value

g, w = g_init, w_init

# iteration

bellman_single_arg(w) = T(w, grid, beta, u, f, shocks)

coleman_single_arg(g) = K(g, grid, beta, dudc, f, f_prime, shocks)

g = iterate_updating(coleman_single_arg, grid, sim_length = 20)

w = iterate_updating(bellman_single_arg, u.(m.grid), sim_length = 20)

new_w, vf_g = T(w, grid, beta, u, f, shocks, compute_policy = true)

plot(grid, g, lw = 2, alpha = 0.6, label = "policy iteration")

plot!(grid, vf_g, lw = 2, alpha = 0.6, label = "value iteration")

return plot!(legend = :topleft)

end

exercise2 (generic function with 3 methods)

exercise2(m_ex, shocks, m.grid, m.u.(m.grid), sim_length = 20)

The policies are indeed close.

35.6.4. Solution to Exercise 4#

Here’s the code.

It assumes that you’ve just run the code from the previous exercise

function bellman(m, shocks)

(; grid, beta, u, dudc, f, f_prime) = m

bellman_single_arg(w) = T(w, grid, beta, u, f, shocks)

iterate_updating(bellman_single_arg, u.(grid), sim_length = 20)

end

function coleman(m, shocks)

(; grid, beta, dudc, f, f_prime) = m

coleman_single_arg(g) = K(g, grid, beta, dudc, f, f_prime, shocks)

iterate_updating(coleman_single_arg, grid, sim_length = 20)

end

coleman (generic function with 1 method)

@benchmark bellman(m_ex, shocks)

BenchmarkTools.Trial: 47 samples with 1 evaluation per sample.

Range (min … max): 105.362 ms … 143.433 ms ┊ GC (min … max): 3.15% … 13.78%

Time (median): 105.795 ms ┊ GC (median): 3.43%

Time (mean ± σ): 107.798 ms ± 7.884 ms ┊ GC (mean ± σ): 3.89% ± 1.65%

█

█▇▁▅▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▅▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▅▁▁▁▁▁▁▅ ▁

105 ms Histogram: log(frequency) by time 143 ms <

Memory estimate: 142.09 MiB, allocs estimate: 151962.

@benchmark bellman(m_ex, shocks)

BenchmarkTools.Trial: 47 samples with 1 evaluation per sample.

Range (min … max): 105.756 ms … 142.888 ms ┊ GC (min … max): 3.38% … 13.26%

Time (median): 106.057 ms ┊ GC (median): 3.59%

Time (mean ± σ): 108.128 ms ± 7.947 ms ┊ GC (mean ± σ): 4.05% ± 1.63%

█

█▆▅▅▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▅▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▅▁▁▁▅ ▁

106 ms Histogram: log(frequency) by time 143 ms <

Memory estimate: 142.09 MiB, allocs estimate: 151962.